A few weeks ago, Steve Saxty – author of the acclaimed “BMW Behind The Scenes books” – kicked off a six-part series that studies the evolution of the BMW grille. It’s obviously a big topic of debate and a subject the author knows like no other having spent 2½ years alongside the BMW design team. In Part 1 which you can read here he looked at how pre- and post-war BMWs were dominated by huge vertical kidney grilles. Now, we move forward into the classic era of the 60s and into the 70s when the modern style of BMWs became established.

Early Post-War Challenges

The BMW 502 sedan was introduced in 1952 with looks that seemed dated even at launch. Large vertical grilles still dominated the car like pre-war BMWs, but that wasn’t the issue. BMW needed fresher-looking cars than this. The car struggled along for six years, almost sinking the company with its slow sales and small profits.

BMW emerged from WWII in poorly condition, scratching around making pots, pans and bicycles. It had fallen hard and fast from being a niche, upcoming maker of sporty cars but was determined to restart car and motorcycle production. Talk to any designer of any era and they will tell you how they are driven to look to the future, but BMW didn’t have a chief designer in the ’40s and ’50s. Head of body engineering Peter Szymanowski could draw and shape a car but since he was an engineer he wasn’t driven by changes in fashion. So the cars that emerged under his watch looked classically good-looking in a late-’30s sort of way but tastes had moved on by now and sales were poor. By the’50s, the company lacked a modern sense of style and with sales being so poor that, just to stay afloat, it resorted to making the Italian Isetta bubble car under license.

Transition to Modern Design

The Neue Klasse sedan solidified the idea of a rectangular frame that leant forward. It served to locate the headlights relative to the kidney grille and create a string face that would dominate the face of BMWs for over 20 years.

Peter Szymanowski retired in ’52 and Body Engineering was now led by Wilhelm Hofmeister. Like his predecessor, Hofmeister was no stylist, but the new man recognized that BMW needed external design help. First up was Albrecht Goertz who styled the 507 roadster and then Giovanni Michelotti, creator of the 700 model, BMW’s most modern looking sedan to date. The Italian designer quickly found favor with Hofmeister after that, especially when his design for the ’61 BMW1500, Neue Klasse turned the company’s fortunes around. Michelotti was a prolific designer but not averse to pitching concepts that BMW didn’t pursue to other competing companies – one of his Neue Klasse concepts with a split grille was subsequently picked up by British company Triumph. Instead of that idea, Hofmeister had preferred Michelotti’s concept of a forward-leaning rectangular frame that encompassed the headlights and held the two kidney grilles in its center. The smaller 2002 followed in the same direction and the E3 New Six large sedan at the top of the range.

Influence of Italian Designers

Michelotti’s star began to wane when Bertone, another Italian design shop, submitted ideas for the E3. Bertone’s new chief designer was the legendary – and recently departed – stylist Marcello Gandini. Hofmeister signed a contract with Bertone for designing the new 5 Series and Bertone, perhaps understandably, wanted to add its Italian own touch to the BMW face. Gandini proposed two large hexagonal grilles for the 5 Series and a facelift of the 2002 but they went nowhere beyond initial sketches and the 1970 Garmisch showcar that BMW reincarnated in 2019.

Paul Bracq’s Era

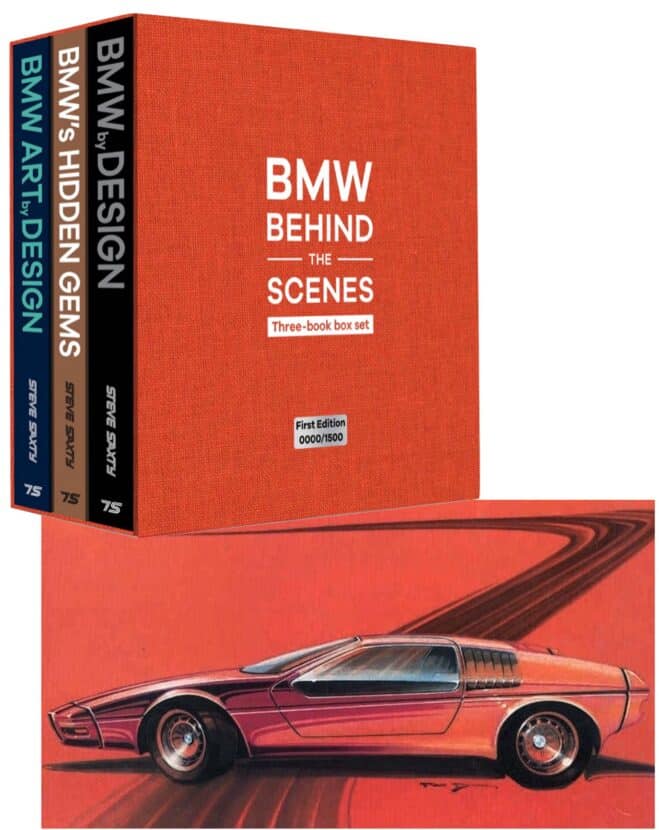

Designer Paul Bracq evolved the front-end style of the 2002 for the all-new E21 3 Series but wasn’t content to keep repeating the same idea. This was his masterpiece, the E25 BMW Turbo, beautifully rendered here in Saxty’s book alongside the pre-war BMW 328. Bracq felt that the old car, with its swept-back grille encapsulated BMW and he wanted to create something that projected the style of a BMW sports car into the future.

The reason why is clear. Against Hofmeister’s wishes, BMW’s board brought in French designer Paul Bracq as the company’s first post-war head of design. The Italians that had been quietly designing BMWs behind the scenes for Hofmeister slunk back into the shadows when Bracq finished off the E12 5 Series and began to display his full creative talent. Bracq’s first all-new car was the E21, the first-gen 3 Series; a sleek evolution in style and concept to the 2002 it succeeded. It retained the forward-leaning frontal aspect that locked up the relationship between the circular lights to the kidney grilles, but Bracq was far too creative to keep repeating the same idea set by the Italians back in the ’60s.

Bracq punched the design community in the face in ’72 when the E25 BMW Turbo was unveiled. Until now, BMW wasn’t regarded as a stylistic trend-setter, but Bracq’s new sports car reinterpreted the two kidney grilles as a pair of tiny nostrils at the tip of a long nose that daringly ran back along the hood while pulling the frame apart either side into two horizontal slits, now freed of containing the pop-up lights mounted above. Bracq had brilliantly remixed the ingredients of the BMW grille and freed himself, and those that followed. The success of the E25 Turbo showcar emboldened Bracq was when he began work on the E23 7 Series sedan and the E25 6 Series coupe. He envisaged the 7 Series as a lean-looking Jaguar-style sedan but his hopes were dashed. Those above him kept pushing for a larger 5 Series featuring the same rectangular grille that dated back to the’60s at a time when fashions in car design were changing fast in the mid-’70s.

Legacy and Evolution of the BMW Grille

The other car under his watch fared a little better. Bracq quickly shaped the body for the E24 6 Series as a stylish coupe that modernized and moved things on from the much-loved E9 coupe. It was natural to try out the front of the E25 Turbo on the 6 Series, but the car was too tall to accept such a low and daring frontal shape. He wanted to lean the whole nose back to make it look more aerodynamic, but Hofmeister and others still wanted the ’60s-inspired shark nose that leant forward. In response, Bracq incorporated four circular lights inside the rectangular frame that he narrowed by partially concealing them with pop-up covers at the top. It was a neat compromise but not possible to manufacture in series production. So Bracq resorted to a conventional shark nose but swept the two halves back left and right with a strong E25-style powerdome across the hood. Growing increasingly frustrated, Bracq quit and left his 95 percent finished 6 and 7 Series to be completed by long-time BMW designer Manfred Rennen.

In his short four-year timeframe, Bracq had broken the mold of BMW design by introducing beautiful details, fresh design proportions and – perhaps of longer lasting impact – freed up the BMW design team across the decades. In future, they would play increasingly different tunes on the relationship between the shape and size of the kidney grilles and the surrounding detail that linked them to the headlights. BMW had a new face and the die was cast for 50 years of change, experimentation and radicalization in design.

What’s Coming In Part 3?

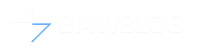

Next, in Part 3 Steve Saxty examines how the BMW grille evolved during the ’80s and ’90s. Part 4 examines radical designs of the ’90s and the calmer creations of the 2000s, while Part 5 examines the large grilles of today and finally he wraps up this special series in Part 6 by looking at the story behind the grille designs of the two Vision Neue Klasse concepts. Saxty’s new book BMW by Design took two and a half years to complete and was written after interviewing numerous BMW designers past and present. It is available on its own or as the BMW Behind The Scenes 3-book set. You can see more about the books here at stevesaxty.com, both book and set are available for immediate delivery.