Frankfurt, Germany – June 2011. BMW was about to wow the world’s automotive press by presenting their vision of an electric future at the Frankfurt Messe. They had developed two concept cars to display, one aggressively styled sports car, the i8 prototype, and one obvious urban transporter, the i3 prototype. The event was to be a dramatic success; the press on hand having been flown in at great expense from around the globe.

The whole BMW management team was on hand to discuss the way forward and while the urban transporter was the steak, the sports car was certainly the sizzle and garnered more than its fair share of attention. I have since tried to imagine what it would have been like if the i8 prototype had not been included in that event, and couldn’t – that car was necessary; the two – the i8 prototype and the i3 prototype – had to be paired, “Beauty and the Burro”, if you will.

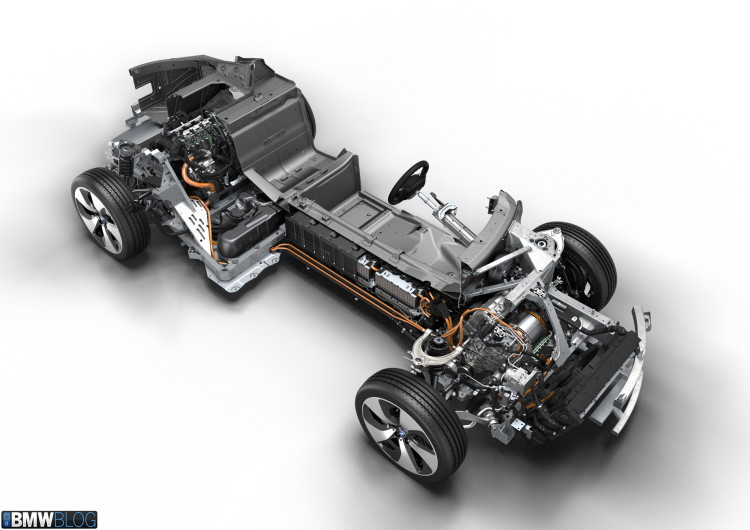

The i8 was a thread to the past inside of BMW’s future promise. It represented the best of BMW internal combustion engine practices, the newly minted ‘B’ three cylinder, part of a family of gasoline and diesel engines announced at BMW’s Technology Day in Munich early April of 2011.

It also housed two electric motors – one where the torque converter normally slots in a automatic transmission car and a completely separate electric motor, similar to, if not the same as, the i3’s, in the nose. There were two complete and separate drivetrains in the i8, the combo gasoline engine and electric motor in the back and the stand alone electric motor in the nose.

The i8 would be a ‘plug-in hybrid’, but unlike the decade old Toyota Prius or the more recent Chevy Volt – which utilize Atkinson cycle gasoline engines – the BMW i8 would be powered by a ‘breathed on’ turbocharged gasoline engine with two electric motors. Emphasis would be on sporting characteristics within the confines of the powertrain. And the i8 would not disappoint.

Twin drivetrains are unusual in cars but are certainly not new – Alfa Romeo having created a number of ‘bimotore’ cars for Scuderia Ferrari to compete against the German GP cars of the mid-1930s and more recently in the late 1950s, when the NHRA banned ‘fuel’ (fuel meaning nitromethane) a number of interesting multi-motor configurations turned up at dragstrips across the USA.

What those previous incarnations of dual motor drivetrains had in common was mechanical linkage between the two drivetrains. And it could be a daunting engineering task to get the two to play well together. With no mechanical connection between the two drivetrains in the i8, BMW would have to rely on software to synchronize them – and in the process eliminate the possibility of unforeseen human intervention, hence no manual transmission, but an automatic that would note the driver’s request and fulfill it if it wouldn’t compromise the health of either or both drivetrains.

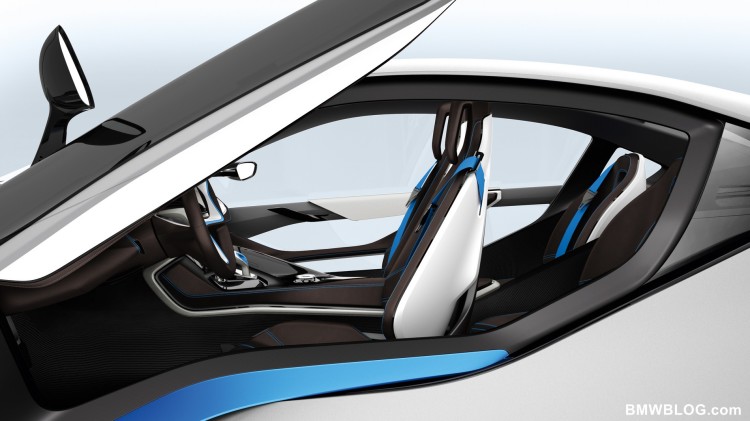

The i8 used the same chassis and external body shell construction processes as the i3 but to a much more pleasing aesthetic standard than the i3 in my mind – with the exception of the Spyder variant, which to my eyes was just a bit awkward (but then I am not a fan of Porsche Targas or Spyders either, so maybe it’s me and not the stylists). The i8, however, did not need to advance beyond prototype stage, but I am truly glad that BMW did build it.

Goodbye BMW i8: We’ll Miss BMW’s Flawed but Ambitious Sports Car

Given the flexibility of BMW’s manufacturing process (the Leipzig plant is a true marvel of production efficiency) it didn’t represent a burdensome opportunity cost to build the i8. Given that there was quite a bit of material available for building the i8 in BMW’s parts bins to absorb the cost of the bespoke bits, it made sense to bring it to production. It was never going to be built in the hundreds of thousands, but given its niche and pricing it should not have been a burden on BMW’s financials.

However, now knowing that the i8 is reaching end of production, one wonders what’s next?